Chapter Text

Jakub, son of Michał, loved Bubbe and Zayde’s bakery.

It was always warm and cozy inside, no matter how much snow there was outside. Whenever he walked inside, he would be hit with a rush of warm air that smelled like butter and yeast and wheat and eggs and honey and every other yummy thing he could imagine.

There was challah and borodinsky, bułka and biały, proziaki and ponchik, lekach and obwazanki, black bread and white bread and sweet pastries and everything in between – all of it smelling so good that just setting foot in the bakery made everyone’s mouths water and their stomachs growl.

He loved watching Bubbe bake – the repetitive motion of kneading the dough over and over and over, the way dough would poof up right before his eyes, the swift movement of her hands as she deftly shaped the dough, the blast of heat from the oven whenever something was placed in it, the perfect golden-brown color of bread and cookies and pastries came out with when they were baked just right.

It was Jakub’s job to carefully poke with one finger each piece of loaf of bread dough to see if it was done rising yet – if the little hole his finger made disappeared, then it needed to wait a little longer. If it stayed, then it was his job to tell one of the adults that it was ready for the next step. Sometimes, Bubbe even let him knead a piece of dough himself! Dough was so much fun to knead – soft and smooth and pillowy whenever he did it just right.

It was also his job to brush the dough with egg wash right before it was ready to go into the oven. He’d take great care in making sure each and every loaf had just the right amount of egg yolk brushed on it – then took great pride in the golden shine each loaf glowed with when they emerged from the oven.

Warm bread straight out of the oven was the best. It would smell so good and nice and warm, but no one was allowed to cut into it – not if it was to be sold, anyway. Sometimes, though, Zayde would sigh at Jakub and Eliasz and Tobjasz’s pleading gazes and throw them a loaf of still-warm bread.

Everyone who lived in the shtetl knew and loved the bakery too.

Some families just bought their bread and sweets straight from the bakery. Others would make the dough themselves and then pay Bubbe and Zayde a little bit of money to use the oven. There was always a parade of children tromping in and out with loaves their mothers had ordered them to take down to the bakery.

They had to be careful to take out their loaf at just the right time, though. More than one child, caught up in their games while waiting, would wait far too long and pull out a charred lump from the oven and would have to return home shame-faced – and then be sent back to the bakery with a handful of kopeks to buy a loaf.

There was always a constant stream of Yiddish being spoken, and he loved hearing about the rebbetzin’s sister’s new baby or what trouble Hersh Leib the carter had gotten himself into this time or how Hersh-the-loaf’s youngest boy was courting Moishe the shochet’s girl.

There was Polish, too, from the goyim neighbors who bought their bread from the bakery, just the same as the Jews – even though the tsar hated people speaking Polish. All the Polish schools had been closed and only Russian was allowed to be taught. Most of the goyim children refused to go to school because going meant learning Russian. Jakub thought they were lucky, sometimes, because that meant they could play all day, but Tate told him to hush the one time he had said it out loud.

Sometimes, when imperial soldiers or inspectors came into town, he could hear Russian in the bakery, too – which even the hederim had to teach, by order of the tsar – and on which the melamed dutifully spent an hour a day.

Languages were fun. Jakub liked wrapping his tongue around Polish – saying good morning to the Poles on his way to heder and asking the goyim customers what bread they would like to buy today.

Even listening to the soldiers speak Russian and trying to copy them was fun, even though they were scary. Everyone was scared whenever the imperial army – or any agent of tsar, for that matter – visited. But even imperial soldiers had to eat and Zayde would never refuse to sell to them, so Jakub practiced his Russian.

Sometimes, he could even hear German if a trader was passing through on his way to Plotzk or Lodzh or Varshe.

Shabbos was for Hebrew, the holy language, though.

And every afternoon on erev Shabbos, each family would walk into the bakery with their pot of cholent, the pot sealed with flour and water, and place it in the oven – where they would stay hot until it was time to be served lunch the next day. Zayde would give everyone a little wooden metal tag to mark which pot belonged to which family, the pots would get mixed up anyway and it was common for families to eat someone else’s cholent recipe. No one really minded when it happened, though, and once you figured out which family the pot really belonged to and swapped them back, all was well.

At least until next Shabbos, anyway.

Even when Jakub had to start attending heder, his favorite part of the day was when the melamed let them out and he could rush over to the bakery. Józef usually lagged behind, or wanted to go to the beit midrash, having some further question or other about the Gemore he wanted to ask the rebbe. Jakub was supposed to walk home with him, but neither he nor Józef ever got in trouble whenever he didn’t.

Beside, if he stayed behind with Józef, he would just fidget the entire time while waiting for the moment Józef was done and they could leave – and Józef would feel bad about his little brother’s impatience and end his questioning sooner than he really wanted. So it all worked out for the best, anyway.

Jakub knew he should be more interested in the details of the Law like Józef was and every now and then he would hang back to listen to Józef and the rebbe, but the bakery was really the best place in the world. Listening Józef ask about who should pay what if an ox gored a cow with a calf or a cow with a calf gored the ox, or who owned a bird running down a line, was boring in comparison. Since when did a bird ever run straight down a line, anyway? None of their chickens ever did anything like that. Nothing could possibly be greater than the squish of dough and the heat of the oven and the warm, sweet smell of baking bread.

There wasn’t a place in this world that was better than the bakery.

“Gnbim, gnbim!” Mame was shouting, pacing back and forth across what had once been their kitchen.

Except it really wasn’t their kitchen anymore. The cholent and the kugel and the challah she had so carefully cooked were strewn and stomped on and scattered all over the kitchen. The floor was strewn with shards of broken plates. Mame didn’t seem to care or notice, though.

When the first shouts had sounded from the shtetl outskirts, Mame had rushed everyone to the cellar. Then they barred the doors. Then, everyone just had to wait.

It had been a very long wait.

Seven bodies, all huddled in the cellar.

Jakub had counted the potatoes and onions, carrots and cabbages, piled up in the cellar one by one. After he had lost count twice, Józef had led him over to where the ice blocks lay, covered in a thick layer of sawdust. And as the Cossacks smashed and shattered and laughed, Józef helped Jakub and Tobjasz practice their letters by tracing through the alef-beis one by one in the sawdust with his finger.

Aleph, beth, gimmel.

Kometz aleph – O. Kometz beth – bo. Kometz gimmel – go.

They both pretended not to hear what was happening above them. Maybe if they acted like it wasn’t happening, it would be true.

Danielek and Sala and Tobjasz and Eliasz had been right next to Jakub. Sala was crying, trembling so hard that Jakub could feel her against him. Danielek had a grip on the stick he and Eliasz had been playing at swords with so tight that it shook. Would a stick be any good against the Cossacks and their real swords?

When finally they came out of the basement, blinking back light so bright that it hurt their eyes, it was as if the world had been turned upside-down. The Cossacks had thrown everything around the house.

Nothing had been spared.

Then Mame had started shouting, “Gnbim, gnbim!” She was still shouting, in fact.

“Thieves, thieves! They’ve stolen everything!”

From the shouts and cries outside, neighbors were coming out from their cellars and their gardens to learn what had befallen their homes.

Jakub hoped that Tate and Zayde were alright. They had been at the beit midrash studying with the rest of the men when the Cossacks had come. As children, Jakub and Józef and a few of the other cousins had had the afternoon and evening to themselves to play.

Mame’s shouting only got louder when she discovered that her prized silver candlesticks and linens, both passed down to her from her bubbe, had been stolen. And at that discovery, she stormed down to the Polish church – Jakub and Józef and Danielek and Eliasz and Tobjasz and even little Sala trailing behind her like little goslings because Mame didn’t want to let them out of her sight.

"How could you let the people do this?" Mame demanded.

“It was the Cossacks,” the priest said, looking so odd in his billowing black robes and white collar. Jakub hoped he would never have to wear anything like that. The collar looked like it itched.

“No, it was the peasants. I heard the Cossacks. And then I heard them. I was in the cellar.”

Jakub had heard them too. He hadn’t wanted to, had tried to focus on what Józef was saying – but he had heard them anyway. He liked hearing Polish, normally. He hadn’t liked listening to it then, though.

“Mame,” Jakub asked as they walked out. “Why do they hate us?”

Mame just looked at him for a long moment, then she hugged him tightly. “I’m sorry, Yankele.”

She didn’t answer his question, and he didn’t ask again.

That Sunday, the Polish priest got up and gave a sermon – and the very next day, Mame’s silver candlesticks, and her linens, came back to her, piled neatly outside the door.

The house and brewery belonging to Feival the kvas-maker that had been burned down would never come back, though. Everyone knew his wife was burning twists of paper in their stove to make smoke so they could keep up appearances that they had plenty of food to cook. Or that was what Chaskiel, newly thirteen years old and thus infinitely wise and all-knowing, had proclaimed, anyway.

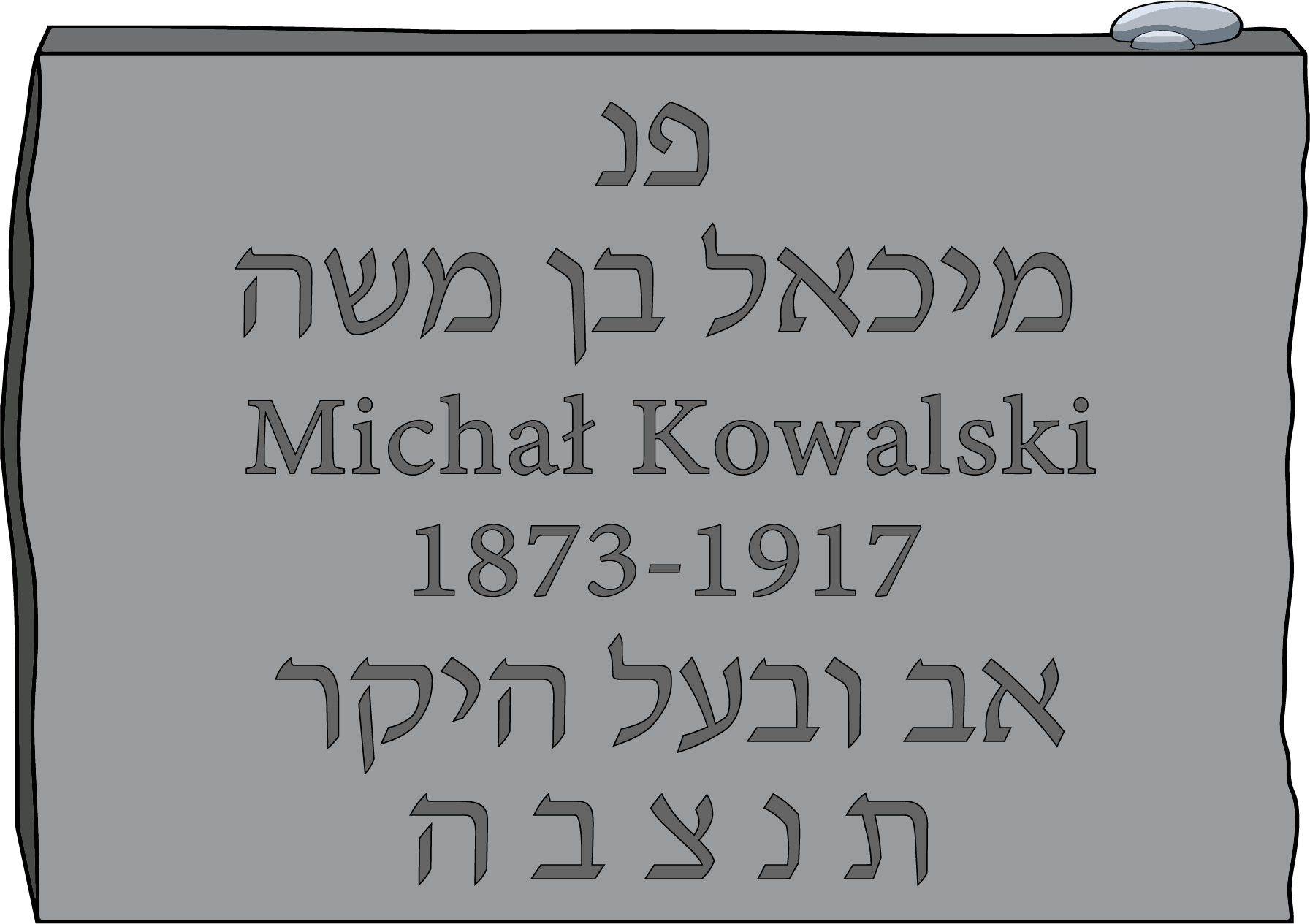

Zayde’s sister and three of children and two of her grandchildren, who lived all the way in a place called Byalistok, so far away Jakub couldn’t even picture it, were dead. Zayde received a letter only two weeks after the pogrom, informing him that she had been killed by imperial soldiers as her husband was hidden by one set of neighbors while the pogromshtshikes, who had also been his neighbors, destroyed his house and stole his belongings. They would never come back either.

The bakery’s windows had been broken, the pantry torn apart like giant rats had devoured everything – though Jakub supposed that Cossacks were even worse than giant rats. They hadn’t done this for food, they had done this just to be mean. The bakery would rebuild. Bubbe and Zayde would make sure of it, and what they said would happened always happened. But in the meantime, there would be no more roast chicken for Shabbos supper. Maybe no more carp, either.

Mame sold her bubbe’s shining silver candlesticks at the next market day.

Jakub turned five, but still didn’t have an answer to his question.

And six weeks later, Tate left to board a ship for America, where the streets were paved with gold and there were no pogroms.

Tate left, and life went on.

For Rosh Hashana, challah was baked in round loaves. Bubbe said it was because the year was without end, one year always seamlessly moving on to the next – just like a circle – and you baked round loaves in the hope of blessing without end in the year to come.

Tate and everyone else from the shtetl who had gone on to America always sent greeting cards and money for Rosh Hashana. The good wishes would be embossed in the prettiest colors and the gold and silver would shine off the page. Everyone would eat apples and honey and they would have lekach for desert and pray for a sweet new year, then walk down to the creek to cast their sins into the water to be swept away out to the ocean.

Jakub wondered where their sins would go, after they reached the ocean. He had never seen a body of water bigger than the Vistula and tried to imagine something like the pond the children went skating on in the winter and the men carved out blocks of ice from – only even bigger. He supposed the ocean had to be big enough to hold everybody’s sins, if they were all being swept out there, and tried to picture a pond big enough to do that. He couldn't, though.

By midday on erev Yom Kippur, every family was already busy with their kappores – a hen for a woman, a rooster for a man. Some people bought white chickens for better forgiveness. A pregnant woman, not knowing whether her baby would be a boy or girl, sacrificed three birds – one for herself and both then a rooster and a hen for her baby.

Zayde let Jakub carry out his own kappores with his own rooster, but he almost burst into tears when he felt its warm side and silky feathers under his fingers. He refused to take his rooster – because he couldn’t help but think of it as his, it was supposed to die for him, after all – to the shochet afterwards and cried and cried until Zayde sighed and sent Józef instead.

There were so many things to do to prepare for Yom Kippur, and Józef followed Zayde around on them all – so Jakub did as well. He helped spread fragrant grass on the shul floor and gathered the reserve of smelling salts and reviving spirits for emergencies. He helped Mame and Bubbe cook the great meal on the eve of the fast – no eggs and garlic allowed – and then savored every bite. And then a day later, the shofar gave one last solitary blast and the Book of Life was sealed for another year.

As soon as the three stars shone in the sky and Zayde had finished breaking his fast, it was time to build the sukkah – where they were to eat all their meals for eight days to remember the journey from Egypt. Jakub enjoyed eating supper under the stars, even if it rained a bit, and felt just a bit bad for the sadovnikim, who didn’t have to live in a sukkah because they needed to guard their crops from thieves.

Simchat Torah was the last and most joyous day of Sukkot, though – in addition to signaling the start of the dreary months of never-ending rain and muddy streets. There were almost no chores and the celebrations lasted long through the evening and into the next day. Every child joined in the procession of all the Torah scrolls, circling around each scroll in turn as everyone danced around the bimah and kissed its velvet cover decorated with tinkling little bells.

Then all the boys would be called up for Kol Hane'arim, even the babies – everyone that could fit under the rebbe’s tallis – and every boy who could be trusted not to set anything on fire would be handed a candle nestled between bright red apples. The whole mass of children and rebbe and Torah scrolls would circle the hall seven times and then there would be treats – lekach cakes with honeyed filling, the apples from the candles would be eaten, gifts of little paper flags cheerfully waved around.

After Simchat Torah marked the season of mud, but by the time Chanukah came around wet, muddy fall had disappeared and a blanket of white had taken its place. Instead of being sucked up to his knees by slippery, slimy mud on his way to heder, Jakub and the other children now walked or skated on the hard snow. Sometimes, if they were very lucky, they would even be given sleigh rides from friendly neighbors. For all eight days of the festival, they would have half-days off from heder and cheerful evenings would be spent with their gambling for buttons and hazelnuts and marbles as the bakery sold what seemed like an endless stream of ponchik and rugelach and babka.

Purim meant the bakery smelled like hamantaschen and poppy and raspberry and apricot and dates and all the other fillings, sticky and sweet. Children from all across the shtetl would crowd around the counter, hoping to be slipped a sample – maybe one that had turned out just a bit lumpy or just a bit too charred to be sold. Purim also meant shalach manos and running around to one house after another, delivering baskets of food – and being rewarded with little sweets and treats for your hard work.

The chant of the Purim Megillah was the most fun of all the holidays, even from the very first words: “Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, who reigned from India even unto Ethiopia, over a hundred and seven and twenty provinces!” And even though the reader had to chant the entire Megillah by himself, everyone always chimed in loudly, “A hundred and seven and twenty provinces!” along with him. Danielek was the helper to the reader and had to chant the names of the eleven hanged Persians in one breath without taking in air, according to tradition and first turned red and then nearly blue in the attempt before stumbling away.

Józef said that he would like to see all hundred and twenty-seven provinces one day. Jakub wasn’t sure how he felt about that. It did sound like it would be an adventure – but it also meant leaving home behind, and that sounded scary. Though he supposed if he went along with Józef to see all hundred and twenty-seven provinces, it might be alright. Józef always knew where he was going.

Then came Pesach and the whole shtetl was overcome with a flurry of preparation. There never seemed to be enough time between Pesach and Purim. Houses and businesses had to be cleaned top to bottom until there wasn’t even a speck of dust or chametz to be found. Mame and Bubbe would send Józef and Jakub out for buckets and buckets of water from the well and armful after armful of wood to boil all the water with. Zayde had to sell all his flour and wheat and barley to the Nowaks, who lived just down the road.

Even the ovens themselves had to be scrubbed clean for Pesach. That was Jakub’s job, since he was so small.

Then every family would gather around at the bakery and it would be a frenzy of flour and water and dough and laughing and jokes, as everyone baked all the matzah they could possibly eat for the next week. Sheets and sheets of flat dough rolled out, and then rushing to poke holes in it with a fork so that it would be placed into the oven just in time – the smell of baking matzah wafting out all along the again-muddy streets. Feter Hersh would mutter that it was so none of the goyim could accuse blood of being baked into the matzah, but Zayde always hushed him before he could say more.

Everyone would gather at Bubbe and Zayde’s house for the Seder – dozens of cousins and aunts and uncles, even a few great-aunts and great-uncles and their children, and whichever stray visitor happened to be in town and needed a table to sit at. They never turned away anyone who needed a seat at their table or a plate of food either, no matter how poor.

Jakub’s stomach would growl before they had made it even halfway through the Haggadah – and his wasn’t the only one. He was overjoyed when Bube and Zayde decided that Sala was old enough to be the one to ask the Four Questions, though. It definitely meant he was no longer the baby – and that meant he was one step closer to being a man, after all. Then, after what always felt like forever, the Seder concluded and they could eat. Matzo ball soup, gefilte fish, potato kugel, roast chicken, tzimmes – all piled on the table to the point it almost creaked under all that weight.

The ending of Pesach meant the counting of the Omer, and when that came to an end, it was Shavuot. Shavuot meant staying up all night studying the Torah at shul – or really, Jakub accidentally nodding off and the sharp jab Tobjasz’s elbows in his ribs to wake up. Shavuot was helping Bubbe mix the fillings – cheese and fruits and more – and the sizzling sound of hot oil on the griddle as batter was ladled onto it.

And then there was Shabbos, week after week – just like clockwork.

For Jakub, Shabbos began on Thursday, when Mame would send him and Józef to the shochet for some shtickel meat.

Everyone knew the shochet’s cats on sight. He would bring home cows’ spleens and intestines for their cats – and everyone would see those cats, the healthiest and fattest of all the cats in the shtetl, dragging them around and around the whole neighborhood with a self-satisfied look on their faces.

Thursday was also the day Mame would go to the marketplace and buy a real live carp that would move into their washing bowl. Jakub loved to throw just a small pinch of breadcrumbs into the water and watch the little mouth open and close in big gulps to gobble the crumbs up. Whenever he could get away with it, he would say that he wasn’t feeling well so that he could stay home, rather than going to heder, and help Mame with the house chores and running errands and Bubbe and Zayde with the bakery instead.

Heder was only half days on Fridays, every boy being sent home by lunchtime. The gravedigger would have started stoking the furnace at the first light of dawn, and by midday the boiler would be full with heaps of heaps of stones heated until they were white-hot piled inside the furnace. And then to the center of town the gravedigger went, where he would thunder, “Yidn in bod arain…in boooooood aaraaaaaain!”

And at the call of, “Jews, to the baths!” the men of the shtetl would turn out in force, the mikveh having already been reserved for women on Thursdays. Fathers led their sons and carried their best clean linen in bundles under their arms. Zayde walked Jaku and Józef to the mikveh every week, since Tate was all the way in far-off America. Beryl, whose own father had died of cholera when he was only a baby, walked with them too.

The steam was so hot as to be nearly unbearable, but when everyone strolled home, it was dressed in their Shabbos best – stiff shirts gleaming white against dark garment. Even the sunset felt like it was more beautiful on Shabbos.

Mame always looked beautiful on Shabbos, wearing her best dress and sheitel. She would stand up and light the candles, whisper the blessing over Jakub and Józef, and then remove her cupped hands from her face and greet them through happy tears.

“Gut Shabbos, mayn ziskeitn,” she would say. “Now, my boys, it’s time for shul.”

Józef and Jakub would walk proudly behind Zayde through the twilight on their way to meet the Shabbos Queen. Zayde in his tailcoat and surdut, Józef with his shiny side-buttoned shoes, and Jakub bringing up the rear.

And after shul was over, there was food. Gefilte fish with fresh horseradish, tzimmes, kugel, twin loaves of challah – all of it backlit with the shining light of the Shabbos candles.

And so the weeks, and months, and years passed – one after another.

Jakub had memories of a time when it was Tate who walked him and Józef to the mikveh and shul every week, when Tate came home each evening and would kiss Mame on the cheek – but Tate was in America now, far far away.

And as the days and weeks and months wore on, Jakub had to try harder and harder to remember what Tate looked like.

Nearly three years after Tate had left, everything changed.

Meite the sheitel-maker’s son had gone to America not long after Jakub had been born, or so everyone said – and over the years had paid for passage for two of his brothers to come join him. He had sent home a photograph with his regular letter and money once, and Meite had proudly carried it around and around the shtetl – first to relatives, then to the neighbors, and then in ever-widening circles until the letter and photograph had reached the entire town.

He had seen the letter. Meite’s son – Sheike, Jakub thought his name was – had been dressed in clothes finer than anyone in the shtetl had ever seen, and standing in front of some fancy background that looked like it could have come out of something the tsar owned.

He had overheard Chaim the tailor muttering something about a broken branch under his breath, but what Jakub asked him what he meant, the man had just shaken his head and thanked him for wrapping up his loaf. Jakub hadn't seen any tree branches in the photograph Meite had carried around so proudly.

Tate never sent a picture home with his letters, which usually came once every month or two. Jakub couldn’t really remember what Tate looked like anymore. Every time he tried to remember what Tate looked like, he just ended up picturing Józef except taller and with a beard. Tate had a beard, just like Zayde – he remembered that much. And everyone, including Mame, said that Józef looked just like Tate. But every time Jakub tried to picture Tate as anything other than letters on a page, all he could come up with were faint impressions of a hug and being picked up high off the ground and a booming laugh and a beard.

Jakub had been taking out the remnants of the Shabbos meal in a tin bucket when Mame shouted so loud that the entire street could have heard her. Even the Wójciks' sow, well-schooled in which trash cans held a welcome change from her master’s regular meals of cabbage soup and potatoes and in the midst of teaching her piglets that same lesson, had startled at Mame’s shout.

The sow wasn't scared of much, including him, and he wasn't scared of her either. She was big, much bigger than him, but she only cared about eating the slop he had to throw out anyways –less work for him. And the goyim didn't care because it wasn't like any little piglets would disappear into a cook-pot while their mother was showing them the best trash cans to eat from. Everyone was happy with this arrangement.

When he hurried into the house to see what was wrong – maybe Mame had hurt herself – he noticed two things.

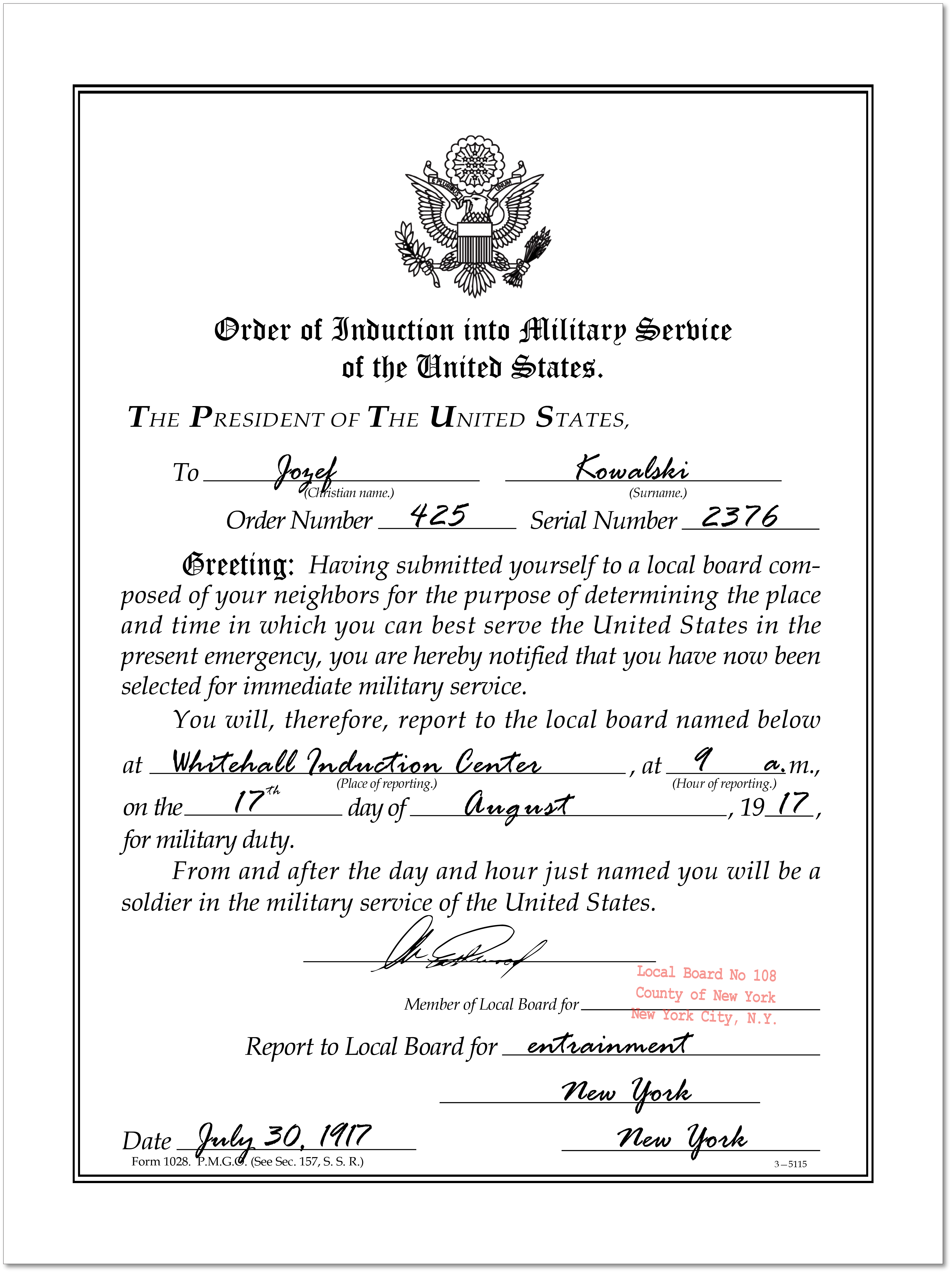

First, that Józef had already beaten him there and was standing next to her, staring at the table. And second, there was a large piece of paper lying flat on the table next to Tate’s letter. He couldn’t read what it said, it wasn’t Hebrew or Yiddish or Polish or even Russian, but the thick black lettering jumped out at him anyway. Hamburg America Line.

Tate had sent a letter.

A special letter, one that was different from all the occasional updates and envelopes of money he had previously sent home.

“Mame,” Jakub asked, because he didn’t know what was happening. “What’s that?”

Mame didn’t answer him though, her gaze still fixed on the letter and her hands trembling.

Instead, it was Józef who spoke up, dark eyes serious. “We’re going to America.”

Jakub frowned a bit. That couldn’t be right. Józef was supposed to go to yeshiva soon – he had overheard Zayde and a few other elders talking about it. He was even smart enough to attend a Russian gymnasium and do well there, Zayde had said – but few admitted Jews, and even fewer universities afterwards. Beside, there was nothing to be learned from a Russian school, anyway. Chaskiel said that they were full of missionaries forcing students to convert to the Russian church.

America was a land of milk and honey where the streets were paved with gold, everyone said. Even so, Jakub had always thought of it as a bit of a dream, a place that wasn’t quite real – something not too different from the world to come.

But they were really going to America?

If the streets really were paved with gold, then at least they wouldn’t get muddy when it rained. So there was that, at least.

Everything happened fast after the letter came.

Mame sold more and more of what they owned until everything they had left fit into her wicker carry-basket, a suitcase, and a small bundle that she held together with a string.

She picked open all the hems of their clothing, even a few seams as well, and sewed money into them.

There were arguments, too – whispers that Jakub wasn’t supposed to hear, but sound echoed oddly in the bakery, sometimes. He never got a whole conversation, only snatches of sentences. Zayde saying something about the air being treyf. Mame snapping something about having a future. He wasn’t sure what they were arguing about, though. Air couldn’t be treyf – no one could eat air, after all.

Tobjasz was nearly green with envy, and made Jakub promise to tell him all about what it was like in America – and to send some gold back so he could show it off to every other boy in town.

Everyone was hustling with preparations for Pesach, which would be in just over a month. And the month before Pesach meant wedding season.

Rwyka was getting married to the Moishe the gabbai’s boy, much to the delight of her mother, and the entire shtetl turned out in celebration.

The niggun made its way down the street and Rwyka was led into the main square by the two mothers, one on each side. Then under the chuppah she and Moishe went, the sheva brachot were said by their friends, then there was the loud CRACK of broken glass as a boot stomped on it.

Then the square erupted in cheering and clapping and laughing and dancing and whirling.

“Siman tov u'mazal tov, u'mazal tov v’siman tov, siman tov u'mazal tov, u'mazal tov v’siman tov y'hei lanu.”

The klezmorim sounded off from their instruments with great enthusiasm – fiddle and the clarinet and the zimbal and the cimbalom and the drugs – and the rebbe started the dancing. Men on one side of the square, women on the other, and children running around every which way.

It was a whirl of chaos and happiness filled with simcha. Mame was laughing as she twirled around and around – the circle she was in opening and closing and letting people in and out, everyone’s arms braced on one another's. Zayde was smiling as he played the fiddle and Bubbe danced around him. The music got faster and faster and faster until Józef tripped over his own feet and took down Chaskiel and Danielek and Eliasz with him.

And then the next morning, they left.

“You’re a man now,” Zayde was saying to Józef. “Take care of your mother and brother.” Józef just nodded solemnly in response.

Feter Dawid could take them as far as Vlatslavek by horse – he had deliveries he needed to make there anyway and, unlike Hersh Leib the carter, Mame wouldn’t need to pay him.

Vlatslavek was crowded and bustling and the streets were even paved. Paved streets were the best thing ever, Jakub thought – because then you didn’t end up in your knees in mud whenever it rained.

Mame said there was a baal shem in Vlatslavek you could buy amulets of protection from that she was going to visit after Feter Dawid dropped them off there. Jakub had never met a baal shem, not that he could remember anyway. One had come, once, years ago, he knew – when Henoch the rebbe’s boy had fallen out of a tree and hit his head badly so that even the doctor had just shook his head and said it would be up to God. Hersh Leib the carter had gotten on his fastest horse and ridden for Vlatslavek. The baal shem had come and prayed over Henoch, and a few days later he was back to normal. He stayed far away from tree branches after that, though.

The baal shem couldn’t save everyone, though. Typhus had still killed Szymon, and Rivke had never lived at all. Józef said that Mame barely left the bed for almost a month, she had cried so much afterwards. The baal shem couldn't stop the Cossacks. There were something things even he couldn't do.

Bubbe shook her head, barely holding back tears as she said to Mame, “Es iz vi vatshing ir geyn in a orn.”

He scrunched his face and looked around in confusion, trying to find the coffin Bubbe said that Mame was walking into. There were no coffins nearby that he could see. He tried to comfort her anyway. “Don’t be sad, Bubbe! We’ll miss this year’s Seder, but I’ll see you next year! We’ll even bring Tate back with us too!”

Somehow that only made Bubbe cry even more as she hugged him, "Oh, Yankele." Her voice broke, and Jakub didn't know what to do other than to hug her back.

Then, all too soon, it was time to go. Mame helped first Jakub, then Józef, their belongings, and lastly, herself up into Feter Dawid’s cart.

Jakub waved and waved at Bubbe and Zayde and everyone else as the horses trotted away, taking him and Józef and Mame with them. He waved until he couldn’t see even the buildings anymore, as they disappeared into the distance, swallowed up by fields and forests.

Jakub’s feet hurt.

“Mame,” he asked, trying not to whine. “Are we there yet?”

They had been walking for what felt like forever. His feet hurt, his back hurt, he was tired, and he couldn’t wait until they went back home. Maybe they could even ride in Feter Dawid’s cart the whole way back from America. That would be nice.

They had walked all day after reaching Vlatslavek, found a sheltered spot a little off the road to sleep that night, walked all day today, and now it was turning dark again. He could see one – no, two – stars in the sky.

The walking had been fun at first. He and Józef had run ahead, pausing every now and then to let Mame catch up and calling out whenever they saw a frog or a bird. Józef had even spotted a turtle and helped it off the main road. Everything had been new and exciting. Jakub had never traveled further than Plotzk before. It had taken almost a day riding on a cart – leaving not long after breakfast and arriving just in time for supper. Józef had even been to Varshe once, back before Tate had left and when Jakub had still been a baby. A boat had taken him there and said it took over an entire day without stopping before it got there.

But now Jakub had had enough adventure and even Józef yawned after now and then. His feet hurt and his shoulders were sore from where Mame had tied the little bundle of belongings he was to carry to his back. Mame said they were to follow the river and it would take them to the border.

His feet hurt. And his legs. And his head. His mouth was dry. Józef yawned again, and Jakub found himself yawning as well.

He blinked. There were little lights hovering in the air over the road, waving back and forth as if in greeting. He tried blinking again to see if maybe that would make them go away, but they were still there. They looked so friendly and welcoming. Maybe the lights would guide them where they needed to go faster.

Mame hissed. "Parfir likhter." Then she grabbed the collar of Jakub's shirt, and Józef's as well – Jakub could hear the slight choking noise he made as the collar pulled him back mid-step. "Va'yomer adonai el ha'satan. Va'yomer adonai el ha'satan. Va'yomer adonai el ha'satan."

And just like that, the lights were gone and Jakub wondered if he had imagined the entire thing.

Then Mame declared that they could rest for the day, and both Jakub and Józef immediately forgot about the lights that had probably been imaginary and nearly groaned in relief as they sat down on the ground so hard that everyone could hear the thump they made all the way back home.

Supper was just cold potatoes and herrings. They had finished off the bread Bubbe packed for them midday yesterday. Mame promised she would buy more when they reached the border town, but he was beginning to think they’d be walking forever and ever and ever.

Last night, Józef had tried to tie a herring to a string to catch some fish for breakfast. They did not have fish for breakfast the next morning and Mame had forbidden him from even thinking about jumping into the river to catch one with his hands.

The river would be their guide to where they needed to go. Well, Jakub hoped that the river would hurry up and get them there soon.

And as Mame pulled out the blankets from her wicker basket to wrap around them, she began telling them a story. About magic and a small Jewish community in far away Praga, which was almost as far as America, and the wonders that had happened there.

“And Rebbe Loew, once he built the golem, carefully inscribed Hashem’s name and put it inside his mouth, bringing him to life.”

“Mame, I thought last time you said the rebbe encircled the golem seven times and chanted a passage from the Torah to bring him to life,” Józef said, grinning.

“Shah! Who is telling the story?”

“You are,” Józef and Jakub chorused in unison

“That’s right. Now, where was I? Ah, yes. The golem was a tireless and faithful servant, fighting to protect and defend the Jews of Praga. He did not need food, nor water nor sleep – only to rest on Shabbos, like any other Jew. They even gave him a name.” Here, Mame paused and smiled.

“His name was Józef!” Jakub cheered, as Józef laughed.

“Yes, they called him Yossele. And then month after month, the golem served as protector until one day, he was no longer needed. So the Rebbe put him to sleep one last time and placed him in the attic of the shul. They say he’s still sleeping there – just in case the people ever need him again.”

“Can we go see if the golem is still there?” He asked, sleepily. Even the rocky ground and the stick poking into his back felt like a nice like the best place ever to lie down at that moment.

“No, Praga is in the opposite direction of where we’re headed. Now, go to sleep, mayn teyer kinder.”

It was a small wooden boat, tied to the side of the river, that the smuggler had led them to. There was no pier, no proper anchor – just a rough rope tied to a stake hammered into the ground alongside a riverbank.

Too many people were on the boat. Too many belongings. The smuggler had ordered everyone to either leave their bundles and baskets and suitcases behind or pay him even more money. Mame had pressed her lips together tightly and handed him an additional ten rubles, on top of the forty she had paid him to get them across the border. Jakub had never even seen ten whole rubles in his life, let alone thirty.

Even so, there were too many people. The boat rocked and swayed and tilted and every now and then, a little bit of water sloshed over the side. Everyone was crouched on the bottom, lying as still as possible – as if not moving would keep the soldiers from discovering them.

No one spoke. Jakub could hear the baying of dogs that sounded too close. The harsh shouts of Russian soldiers – or maybe the Germans? It was too far away to make out exactly what they were saying, but they sounded too loud and angry and close. Then there was the sharp crack of gunfire.

There was a splinter in his hand, he was pressed so hard up against the wooden floor of the boat.

He could see Mame clutching the amulet the baal shem had given her. He could hear he whispering, “Shema Yisrael, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai echad,” over and over and over. Józef had a grip on his hand so tight that it hurt. One of the other children in the boat had started to cry and someone harshly hushed them.

The night sky was dotted with stars but Jakub couldn’t see any of them, laying face down as he was. How could anyone count all of them like the psalms said? The sky was just too big.

After what felt like forever and a day, the boat reached the other shore and the smuggler guided them through the woods until they were on the outskirts of a city. Throughout all that, no one dared make a sound still, even when a man tripped over a tree root and came up bleeding from the ground.

Mame led them down one alley after another, pausing every so often to find a torch to squint at something written on a piece of paper before continuing. Finally, they stopped in front of a house. She knocked on the door with one shaking hand as her other arm held Józef and Jakub to her tightly to her side.

An old man opened the door. Warm, dark eyes, a thick gray beard, and a broad smile greeted them. Mame shifted her weight a bit, trying to smile, but before she could say anything the man said, “Come in, come in.”

Mame kissed her fingers and then touched the mezuzah as she passed through. Józef did the same. Jakub tried to but he was just a bit too short to reach it all the way. The man smiled at him though, so Jakub didn’t think that he was in trouble.

Inside the house was a woman, about the same age as the man, and a young boy who looked a little older than Jakub but younger than Józef.

The boy looked at Jakub, wide-eyed. Jakub stared back at him. Józef was looking around the room with interest.

After introducing herself and her family, stammering only just a bit, Mame said to the man, “We were told you can help us.” She reached into her pocket for more money, but the man smiled and shook his head no.

The woman put her hands on Mame’s shoulder and asked, “What can I get you?”

They were led into the kitchen, where Jakub and Józef immediately placed themselves in front of the stove. How wonderful it was to be warm.

Then plates of kugel and bowls of soup were set out in front of them, and the woman smiled encouragingly at Józef and Jakub. “Go on. Eat as much as you want.”

Mame managed a rought, “Thank you,” as Jakub and Józef tore into the food in front of them. It was food! Good food! Bubbe’s food was probably better, he felt, but this was worlds above cold potatoes and herring and tasted like the best food that had ever existed to him at the moment. They were even given cake.

Before he knew it, he had fallen asleep in his chair and someone was guiding him up a set of stairs.

“– will be happy there. Don’t you worry, now. Everything will be alright – you’ll see,” someone was saying.

Then he and Józef were led to something soft that they collapsed onto, and then – sleep.

They woke just after sunrise the next morning. The woman made them all a hearty breakfast and packed them extra food to take with them for the train and while they waited to board their ship.

Mame tried to insist on paying them for all the help they had given, but she was refused.

“Do a mitzvah for somebody else, when the time comes. That will be payment enough.”

Józef and Jakub marveled at how fast everything moved by them on the train. Just – zip! And another tree, another field was gone. Trains had to be the fastest things ever, and the coolest. You didn’t have to do anything, didn’t have to feed or brush them. They just ran on their own.

He thought that the second coolest thing was listening to the train people speak German, he had never heard so much German before – only caught it a few times from traders passing – but he could almost understand it anyway.

And before they knew it, only a day later, they had arrived at Hamburg. Someone was waiting for people with ship tickets at the railway station and escorted a group of them to a camp on a trolley. Mame said that they were lucky to sail out of Hamburg, because other places, they would have had to pay for each night they spent there.

It was called Auswanderer-halle, the people working there told them, and it was huge.

The camp was divided into three areas, Aleph, Bet, and Gimmel – A, Be, and Ce in German. Area A was the unclean section where everyone was sent first and got baths with lye soap and new, clean clothes. Afterwards, if nothing was wrong, they would be moved to Area B – where they would sleep until their ships came and doctors checked on them every other day. All the sick people were kept in Area C, away from everyone else.

Auswanderer was neat even though there were so many people, more people than Jakub had ever seen in his life – and so many new languages too! Despite that, it was a neat place well-ordered. Camp workers made sure that everyone had new clothing, and even would give a few marks, the German ruble, to anyone who didn’t have enough money. And if the clothing ever ran out, there was always more by the end of the week – just like magic. And, even better, the food they served every day was actually almost good.

The people at the camp told them what to expect, too. “Sea water is salty and undrinkable,” one camp worker explained to a group of them in Yiddish. “Therefore the ship has to be supplied with drinking water when still at shore. This water is called sweet water. You cannot drink the sea water while you are on the ship.”

Jakub said, “I can’t wait to see the look on Tobjasz’s face when we go home and I tell him there’s water that you can’t drink. He won’t believe me – maybe I should take a little bit of it back so he can see.”

“We’re not going back, Jakub,” Józef said quietly, frowning at him. “America’s forever. We’re never going back.”

Jakub blinked. That couldn’t be right. They had to go back, they had to see Bubbe and Zayde and everyone again. Forever was – forever. Unable to help himself, he started to cry and Józef scrambled to find something to console him with – which, turned out to be begging the camp cooks for an apfeltaschen.

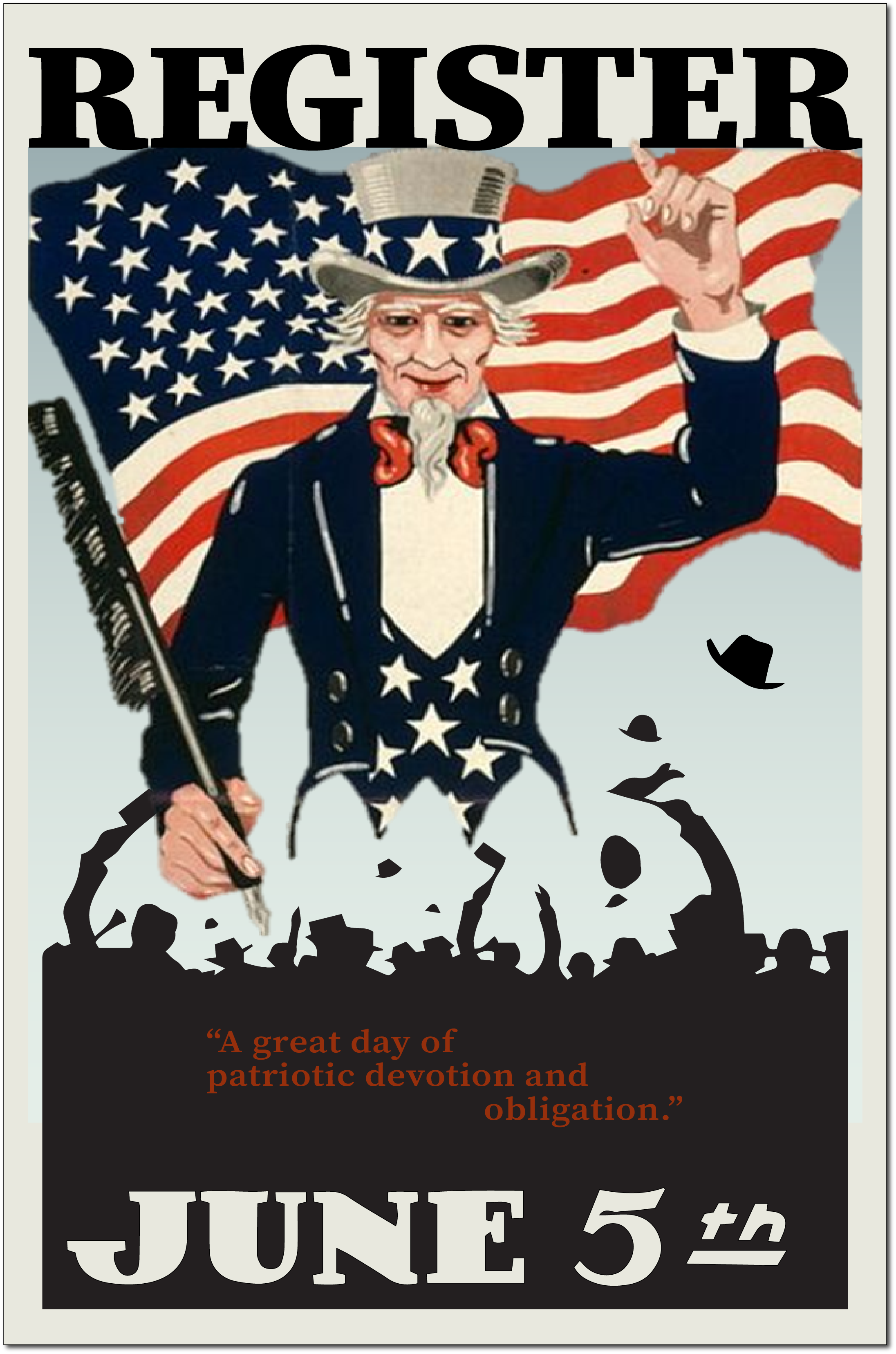

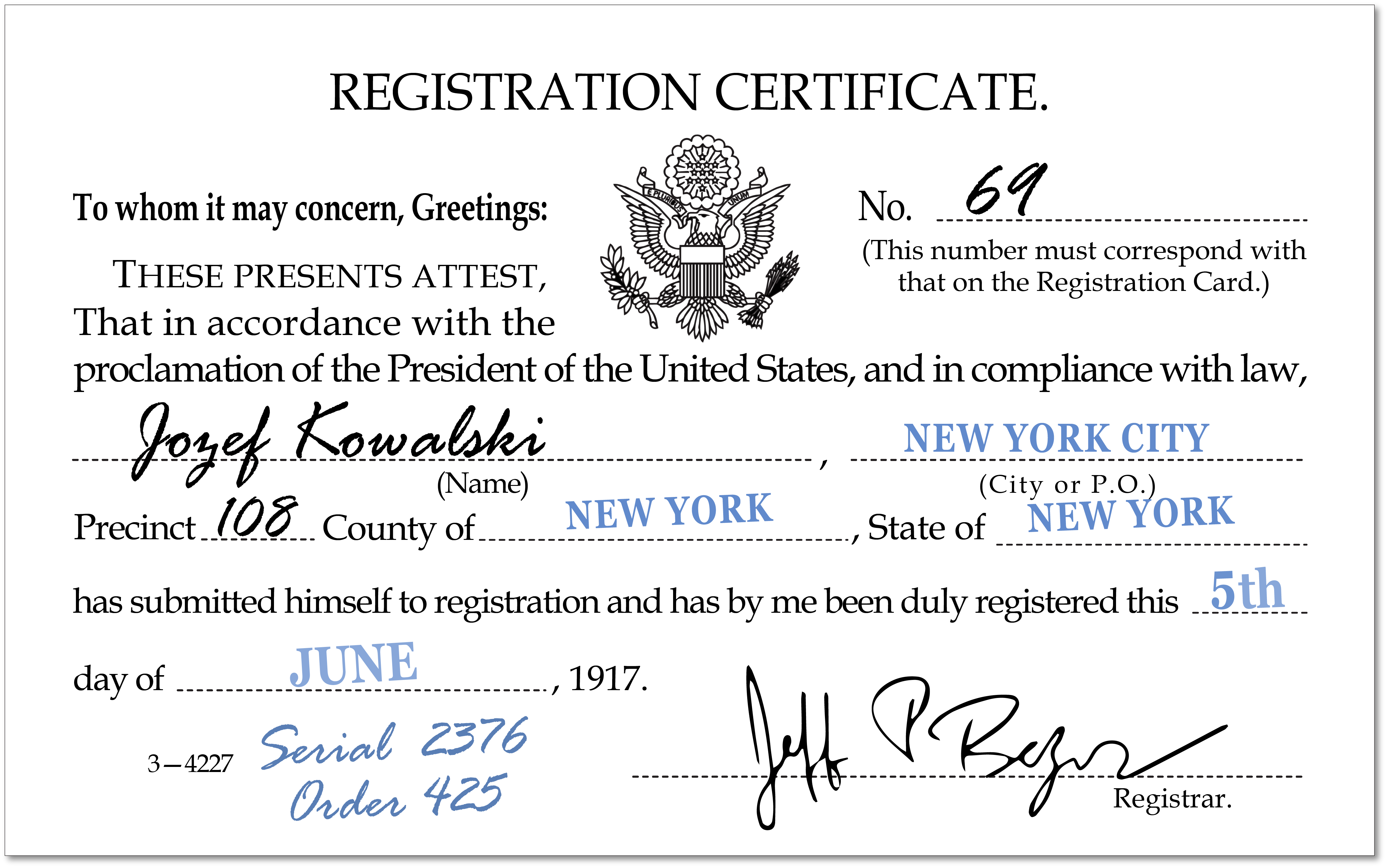

On Shabbos, Józef, with nearly zero time to prepare, became bar mitzvah and read the parshat and haftarah at the camp shul without making a single mistake, with Mame beaming proudly and Jakub waving so excited that he nearly knocked Józef over when he went to hug him afterwards.

The entire Jewish portion of the camp gathered together for the Seder, one evening. It was impossible to completely remove chametz from the camp, not with thousands and thousands of people there – but surely there was not even a single speck of chametz left in the Jewish quarter of the camp.

Not just one, but ten pieces of the afikomen all around the camp dining hall – the first twenty children to find them got an orange. And every child under the age of ten asked the four questions as one. It was a good thing that everyone already knew what the four questions were, because otherwise, he didn’t think anyone could have understood exactly what had been said, it was such a jumble.

The very next morning, the three of them woke up and got in what felt like the longest line in the world. Mame with her wicker basket, Józef with his suitcase, and Jakub with his little bundle. After what felt like days of waiting, they finally reached the front of the line, where a man asked Mame a bunch of questions.

Where was she going? Who was meeting her there? How much money did she have with her? What was her occupation? How old was she? How old were her children?

Jakub was about to speak up and say that he was seven, almost eight, but Józef grabbed his shoulder and shook his head no at him – so he stayed quiet.

There were even more questions that he honestly stopped paying attention to after a while, but finally, the man stopped asking Mame questions and scribbling in his big book and told them to step away so that another man could examine them.

Jacob yelped as that man jabbed something metal at his eye and felt like he was trying to peel off his eyelid, but nearly as quickly as it had taken him by surprise, that part was over. Then his scalp was inspected with a comb and the men put a little round metal thing on his chest that connected to his ears with a tube.

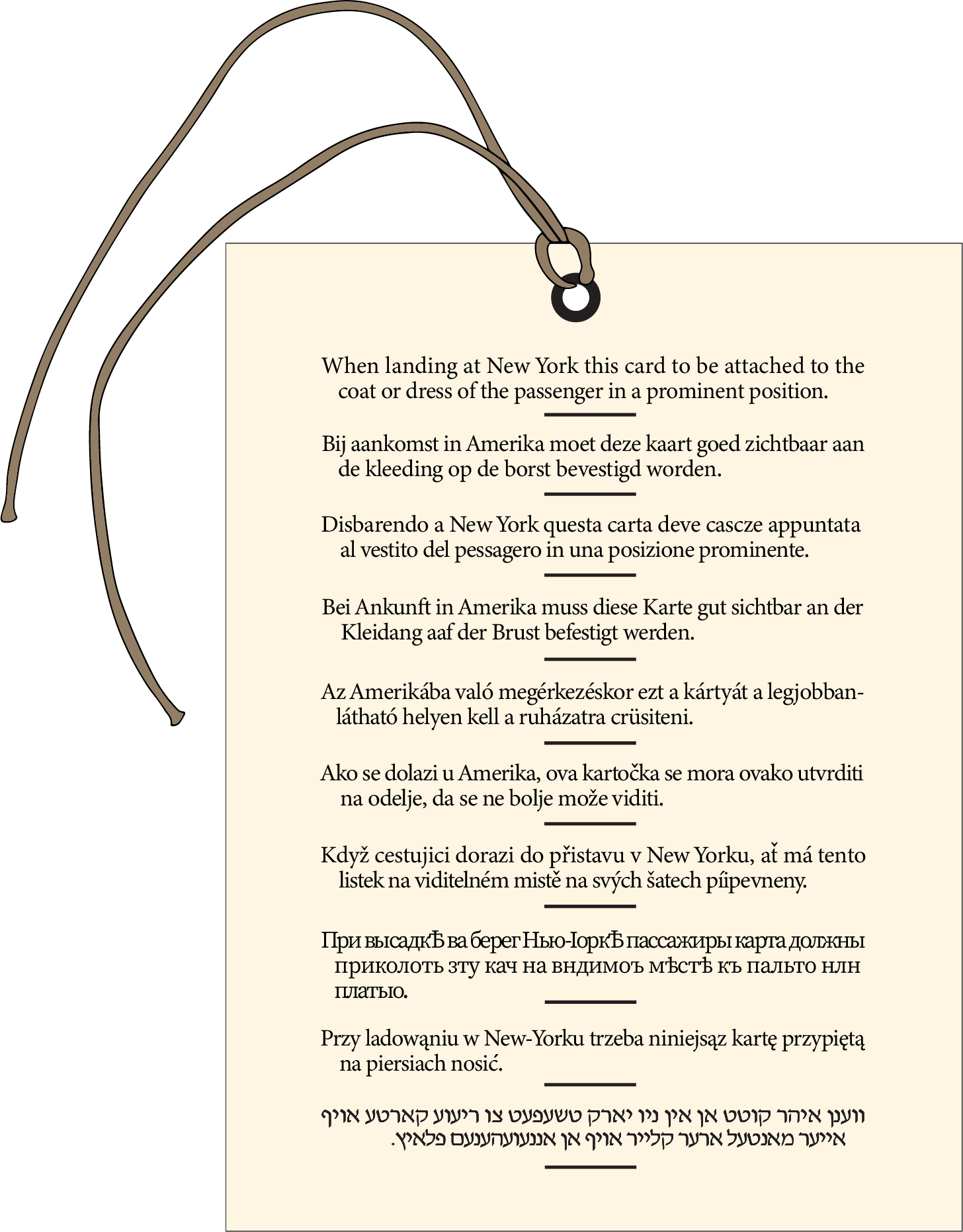

Then there was a sharp poke in his shoulder, but after that it was over for good and each of them was handed a card. The second man bent down and sternly told them, in accented Yiddish. “Do not lose this. Bad thing if lost.”

Finally, after all of them were declared satisfactory, they were allowed to proceed on down to the harbor to board their ship.

A trolley took them down to where they would board their ship, four horses neatly trotting over the cobblestone with perfect timing as Józef and Jakub marveled at the pretty houses they passed by. Mame just sat on her seat in silence, clutching her wicker basket.

When they finally arrived at the harbor, the air smelled weird. Sharp. Like fish too, and not the tasty kind.

Then, Jakub forgot all about the air and the fish because he saw the biggest thing he had ever seen in his life. There was water, so much water, as far as the eye could see until it disappeared into the sky. He hadn’t known that much water even existed in the world. It was just so big and it was everywhere.

And floating on top of the water was the biggest and prettiest boat Jakub had ever seen. It loomed so high he wondered that it didn’t scrape a cloud. This was the most amazing thing he had ever seen.

Józef had spotted it too and his eyes were nearly as wide as Józef’s. Then, without even glancing at each other, they ran down the pier towards the boat, feet echoing on the wooden boards as Mame hurried behind them.

The boat was crowded, just one big floor of everybody. Men and women and children and so many different languages. It was dark and cramped and Jakub felt a bit like Yonah, trapped inside of a fish. He hoped that the boat wouldn't throw them up like the fish did, though. That would be messy.

Cups were given out for sweet water, one for each person. But there just weren’t enough cups. So at night, Jakub would creep under somebody’s bunk and scrounge for extra cups. Józef tried to do that, but he was too big and had to pretend like he was crawling on the floor because he wanted to throw up.

Everyone threw up, though. The ship rocked and rolled from one side to another, even when you were trying to sleep. Men fought over who got the top bunks and hammock, because being on the bottom ones meant that if someone above you threw up – well, you just had to pray that you would be lucky that night. It all stunk, worse than anything he had ever smelled before.

Every morning, a sailor would burst in and shout, “Rouse! Rouse! Rouse!” and everyone would have to quickly wake up and get out and go up on deck. It was also nice to breathe clean, fresh air for a bit, though – and most of the children on board would quickly organize themselves and begin a game of tag.

They were fed two meals a day. Breakfast was coffee and black bread. Supper was boiled potatoes and herrings and, if they were lucky, a roll. Mame always gave her herrings and rolls to Jakub and Józef, and Józef always gave his herrings to Jakub. What felt like the entire ship sat down together at the longest tables he had ever seen for these meals. They just went on forever and felt like they spanned the entire length of the ship.

Life quickly reduced itself to trying to explore every nook and cranny of the ship. Maybe if they got lucky, they might find something cool. The sailors sometimes got annoyed at them, though, if they were caught poking around somewhere they weren’t supposed to be. They slept a lot, whenever they could, just because there wasn’t much else left to do when you were hungry and tired and feeling faintly sick all the time.

After four days, Jakub had gotten excited at seeing a faint smudge that he was sure was land, far off in the distance and shouted, “America, that’s America!”

Marzena, fourteen years old and from Varshe and bossy as a result, had rolled her eyes and said, “No, dummkopf, that’s England.”

Jakub wasn’t sure where England was, but he didn’t care. They were near land!

Just the chance to walk on ground that wasn’t constantly moving under them would be the best thing in the world.

Once they’d gotten off the ship and onto a smaller boat – he had never seen such a big city and so many people and a clocktower looming over it all as they pulled into the harbor – he discovered something even better.

They would have food and real beds that didn’t stick of throw-up – though he and Józef would still have to share – and they would even be allowed to bathe and they could drink as much water as they wanted.

And then, the next morning, they were shepherded to a railway station and got inspected again and boarded yet another ship.

Jakub was really getting tired of people poking at his eyelids.

This time, when he saw land, it really was America. Everyone buried in the belly of the ship had to wait a bit, and then they all crammed onto a ferry. It would take them to a place called Ellis Island, people said.

He didn’t really know what Ellis Island was, or who this Ellis was, but he had heard stories about Ellis Island on the ship. Everyone seemed to know a story about something scary happening there, about what would happen if they found you “deficient” – one boy had said that those people just got swallowed up by the earth and were never heard from again.

Jakub hoped that wasn’t the case.

On the ferry, each of the children were given little paper flags – red and blue and white. It was definitely more colorful than the tsar’s flag of yellow and black and white. And prettier patterns, too.

And then – the most beautiful thing he had ever seen.

“It’s Lady Liberty!” a man cried out

Everyone crowded to one side, trying to get a better view of her to the point that the ferry began to tilt to one side. The ferry captain shouted at everyone to spread out, but no one obeyed. Mame shouted for Józef and Jacob to stay in her sight so she didn’t lose them – but they didn’t really listen to her either. They were too busy jumping up and down trying to get a better view and cheering and waving their flags around. One boy tried climbing onto the railing to get a better look and nearly fell over-board – only to be hauled back by the scruff of his coat just in the nick of time.

She was so big and so tall and her light was so bright and shining. America! This was America!

When the ferry finally arrived at what was probably Ellis Island, soldiers greeted them. As they walked off the board connecting the boat to the ground, barking orders and issuing little pieces of paper at them.

No one knew what the soldiers were saying but, through motioning, it was made clear to them that they were to tie the little paper onto their clothing.

And then, they waited in line. It was a long line. His legs started to hurt standing in line and sometimes he plopped down on the ground until it started to move again.

Sometimes the line stood still for what felt like forever. Sometimes it moved fast, almost at a run. Other times, it krept along so fast that he bet baby Blima, who had yet to really begin to crawl, could have moved faster.

He had no idea how much time had passed, but after what felt like forever, they finally walked into the big brick building.

The first thing he saw were stairs. Really tall stairs. He had to bend his head back until it nearly touched his neck to see to the very top of it, but even then, it felt like there were just more stairs.

They started climbing anyway. What else could they do?

The stairs were tall, taller than anything he had ever had to climb before – but no one seemed to dare to stop, no matter how heavy the burden they were carrying.

At the very very top of the stairs, men lined both sides of the hallway. They were dressed in uniforms and looked a bit like soldiers, but someone else said that they were doctors. Jakub had never seen a doctor that looked like that before.

One man in front of them wept as the doctors pulled him aside and used a piece of chalk to write something on his coat. It was a low, keening sound, joined by the cries of his five children and his wife.

Jakub wished that he could block his ears from the crying. He hoped that didn’t happen to him and Józef and Mame.

Some of the other officials wore uniforms. These men looked a bit like train conductors, with fancy peaked hats and dark blue uniforms. They were very short with everyone and kept barking, “Move! Move! Go! Go! Come!”

Jakub had no idea what they said, but he guessed what they wanted each person to do by the way their fingers pointed.

He yelped as someone tried to peel his eyelid off, again. But after a few minutes of the doctor poking at him, he was let through. Then it was Józef’s turn. Mame took a few minutes longer, but she was cleared as well.

Then, they were pointed to “The Great Hall” and it was huge. He had never seen a single room this big before. It was loud, too – thousands of voices echoing and bouncing around the hall. Wooden benches and metal railings were everywhere, so they took a seat. And then they waited. No one knew how long they had to wait. It was just an endless crowd of people speaking dozens and hundreds of different languages. Everyone was just waiting. Waiting for what, he didn’t know. But there was a whole lot of waiting.

Józef and Jakub’s stomachs started growling, and Mame just sighed and carefully counted a few marks and rubles and told them to go buy food. When they made their way downstairs and tried to buy food, the storekeepers shook their head and wouldn't take their money. They pointed upstairs, and one of them spoke enough Yiddish to tell them that they needed to change their money. So Józef and Jakub wandered back up and found a counter with a big chalk board with a bunch of numbers.

He looked at Józef, hoping that he knew how many dollars was a mark and ruble. Józef just looked back at him, wide-eyed. Finally they just went up to the man at the booth and shoved the money Mame gave them to him, hoping that the amount would end up right and be enough to buy food with.

It was and oh it was so good to eat something that wasn't hard black bread and herrings. He never wanted to eat another herring again in his life. They got a little bit of food for Mame as well and brought it back upstairs with them.

And then they waiting some more.

Finally, after what felt like two entire forever, their names were called, and Mame ushered them up to the immigration clerk, who sat on a tall stool behind a tall desk and peered down at them. He tried not to hide behind Mame or Józef at that hard stare. The man looked scary. Józef moved himself just a bit in front of Jakub, shielding him a bit.

The man flipped through pages that Jakub couldn't read, and then asked a storm of questions. Another, younger man stood beside him and asked Mame in Russian what language she was most comfortable with, then started translating in what the first man was saying.

Even in familiar, conforting Yiddish, it was a lot of questions.

What is your full name? How old are you? What is your occupation? Are you able to read and write? What country are you from?

What is your final destination in America? Do you have a ticket to your final destination? Who paid for your passage? How much money do you have? Have you been to America before? Are you meeting a relative here in America? Have you been in a prison, charity almshouse, or insane asylum?

Are you a polygamist? Are you an anarchist?

Jakub didn't know what an anarchist was. Or a polygamist. He asked Józef, because Józef knew everything, but he just shrugged in confusion because he didn't know either.

Are you coming to America for a job? What and where will you work? Are you deformed, crippled, or ill in any other way?

Mame answered the questions carefully, her voice shaking just a bit but not too much. And then, nearly as fast as it had started, the questions were over. The man stamped their cards and handed them back to them and briskly waved for them to move aside so the next family in line could come forward.

Even more officials – just how many people worked here? – then led them outside, where a chain link fence separated new arrivals from the family members that came to pick them up.

The officials asked Mame to identify which of the people was her husband, and Mame instantly pointed to one man with a beard, his dark curly hair showing the first streaks of gray and one hand holding a silver pocket watch. The pocket watch almost fell out of his hand at the sight of them and he rushed over, pressing his face up against the fence and shouting for Mame.

Jakub looked at him in fascination, trying to match this man up to his faint memories. His eyes did look a lot like Józef’s – and his own – he supposed.

“Michał,” Mame was nearly in tears as she hugged him and he spun her around. “Oh, Mikhe.”

The officials opened the gate to let them through and, just like that, they were in America.

Notes:

"Wait, but Jacob's not Jewish in the movies?"

Well, it's my fic and I can headcanon him how I want haha. Also, there's a ton of historical background I'm drawing from! All of Jacob's backstory is otherwise entirely plausible! Further details and Excited Historical Nerd babbling can be found here, in Map of the Modern Wizarding WorldLanguages! Young Jacob uses the Yiddish name for places because Yiddish is his native language. Plotzk is Płock, Lodzh is Łódź, Varshe is Warsaw (Warszawa in Polish), Byalistok is Białystok, Vlatslavek is Włocławek (plus they would have all had official Russian names at the time as well). And yes, the shift from Yiddish to Polish between child Jacob and adult Jacob are on purpose! Aren't geopolitical linguistics fun!

I feel bad for putting Jacob through the wringer like this, but the first movie clearly indicates that he is All Alone and the only way you get that is by everyone being dead. Which is why Jacob doesn't have more siblings even though family sizes for his demographic and time period tended towards 10-12 children, because then I'd have to kill them all. So he just gets the one brother Canon Says He Has and let's all just handwave the rest in the name of sparing him more trauma - shall we? For what it's worth, rest assured he gets a very happy second half of the 20th century. He just...needs to get there, first.

The Statue of Liberty changes color throughout this because in 1909, when Jacob and his family arrive, it hadn't finished oxidizing yet! It about halfway through oxidization and won't finish until the mid 1920s, so the overall color is quite literally shades between the original copper and the greenish-blue patina that we know and love today.

Chapter 2: 1909-1926

Notes:

Note: This chapter formerly hosted Queenie's chapter, which has now been split into its own work and replaced with half of Jacob's story because I realized with 50K chapters that I bit off more than I can chew and was essentially trying to stuff 25 lbs of fic into a 5 lb bag, but didn't just want to delete this chapter and lose the preexisting comments. Queenie's story is now located at I am but dust and ashes

(See the end of the chapter for more notes.)

Chapter Text

“Land on Saturday, settle on Sunday, school on Monday.” Or so the saying went.

Joey Baldazzi had been rolling his eyes as he had said that. “You Jews. Land on Saturday, settle on Sunday, school on Monday.”

Or at least that was what Henry Rogarshevsky, who had been in America for nearly a year now, had said Joey had said. Jakub hadn’t been able to understand Joey, just that he was rolling his eyes and shaking his head and laughing. Henry had told him in Yiddish what the other boy was saying.

But, just like Joey had said, bright and early on Monday morning, Mame had walked both him and Józef to school.

Józef wasn’t in the same class as Jakub. He was too old, Henry said, and all the older immigrant kids had their own steamer class for six months before they were shoved into the main classrooms.

Everyone else started at the first grade.

The classroom was cramped and crowded, even more so than the heder had been. There were three, sometimes four, children jammed on a bench that appeared to have been really designed to only seat two.

But somehow, everyone fit on the wooden planks. Then the teacher said something in English and everyone came to attention as she came to a stop in front of the desk where Jakub was sitting with Henry and another boy.

She was a tall woman, dark haired, dressed neatly in plain calico. Young, maybe. Certainly younger than Mame. She was saying something to him, but he had no idea what.

Henry prodded him in the side “That’s Miss Rodman. You’re to show her your nails – she checks to make sure everyone’s hands are clean each morning. And tell her your name.”

Jakub offered her his hands and she turned them over, inspecting first the front, then the back. “Ikh heys Jakub Kowalski.”

Miss Rodman shook her head firmly. “No. You.” A finger poked his chest as she said loudly and slowly, “are Jacob.”

And just like that, he had a new name. Henry told him later that, aside from whispers to help kids like him fresh off the boats, anyone caught speaking any language that wasn’t English – Yiddish, Italian, Polish, Russian, it didn’t matter – in school got a caning.

"I pledge allegiance to my Flag and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all,” was the first real sentence in English that Jakub learned at school.

The streets weren’t paved with gold, after all, and Jakub supposed that Tobjasz would just have to be disappointed that he couldn’t send any back.

Mame found a job at a shirtwaist factory. At night, she and the other women of the tenement would sit at the kitchen table, bent over piecework that would be sold to the stores and factories. Eighty-four cents for a dozen trousers, eight cents for a round coat, and ten cents for a frock coat. Sometimes, once Mame had assured herself he and Józef were ready for school the next day, they sat at the table and helped cut and sew and finish as well.

Tate worked at a tailor shop by day and peddled fruit on a pushcart in the early dawn and late evenings. Apples in the fall, lemons and oranges in the winter, cherries in the spring, watermelon and peaches in the summer.

There were over a dozen people who shared the three rooms they lived in – a bedroom, a kitchen, and a living room. Mame, Tate, Jakub and Józef, Mr. and Mrs. Rogarshevsky and their six children, and five boarders. He and Józef shared a bed and counted themselves lucky for it – all four of the Rogarshevsky boys had to share a single bed.

Yiiddish was as common as English in the neighborhood – mixed in with Polish and Russian and even some Italian and so many other languages he couldn’t even figure out which was what yet – there wasn’t a single boy who could go a day without a bubbe in a tichel giving him and his friends a scolding for whatever recent stunt they pulled, threatening to tell their mothers if they kept it up. Except for Józef. Józef was a good boy and spent most of his days, when he wasn’t at school or selling newspapers or helping Mame and the other women with piecework, at the library – the giant lions standing guard over him.

Jakub went exploring instead. He learned English, first the words and then how to sound the words just right so that the teachers stopped looking at him funny – and then, once he mastered that, he tried to copy English the way the Russians or the Poles spoke it. Then he tried to figure out how the Italians spoke, and their languages. Joey would laugh a bit, but then correct him on his pronounciation or when he got a word wrong.

After a long day at school trying not to fidget too much at their desks, because otherwise they would get smacked for not paying attention, he and the other neighborhood boys would wander around the neighborhood and learn which grocers and bakers were willing to hand a boy some small coin or treat in exchange for running errands and other small chores. He quickly learned that the store owners liked him better if he could talk to them in their language. Mr. Schimmel was his favorite, though. Sometimes, if they asked nicely enough and did a good enough job, Mr. Schimmel would even give them one whole knish, all to themselves!

There were so many people living here and so many tall buildings – more than he had ever thought was even possible. Laundry lines stretched across the street, and the clothes were never quite all the way white when they dried, but they were still clean enough. Laundry was a whole day affair left for Sundays, when nearly everyone pitched in. Buckets and buckets of water had to be hauled up four flights of stairs, and then coal too so that it could be boiled. Everyone knew not to run around too much on Sundays, and especially not to knock a clothesline over – because then they would be in for a beating for sure.

Sometimes, Mame wouldn’t get home at work until late at night, because someone else had asked if she could cover their shift. Mame always said yes, because they needed the money, but he and Józef were usually asleep by the time she came home, no matter how hard they tried to wait up for her.

On those nights, sometimes Jakub woke to the soft creak of Mame sitting by the side of his bed, combing through his messy hair with a finger and softly singing to him.

“Yankele vet leirnen Toire,

Toire vet er leirnen,

Briwelach vet er schreiben,

Fil gelt vet er fardinen.”

It was Shabbos afternoon, and Shabbos meant that Mame only had to work seven hours at the shirtwaist factory instead of twelve. Józef and Jakub were always there at the factory to pick her up at five o’clock to walk her home. No matter what friends they had to say goodbye to, no matter how good a library book was – they would be waiting in front of the factory for Mame by five o’clock.

But when they got to the factory, there was a cloud of smoke hanging over the building. And all the way up there, by the windows, was a press of faces. The flames from the floor below were beating in their faces.

Jakub could almost feel the heat of those flames even all the way from the ground.

"Call the firemen!" they screamed.

"Get a ladder!" they cried.

There was the siren of a fire engine off in the distance, coming closer and closer. More sirens sounded from several directions.

"Here they come," the crowd was shouting. "Stay right there!"

Some of girls were running down the first escape, but then the metal gave way with a sick groan, twisting and collapsing as it bent and buckled and pulled away from the building. The people screamed. The metal screamed. And then there was no more screams. Not from them, anyway.

One girl climbed out onto the window ledge from the second highest floor. The ones behind her tried to hold her back. And then she just – dropped into the air.

Jakub had thought she had to just be a bundle of clothing, at first. It couldn't be a person. It had to be a doll, or a bunch of shirtwaists bundled together.

Then came the harsh thump.

Another girl was climbing out onto the window sill, others crowding beside her. And then she fell – waving her arms, trying to keep her body upright until the very last moment.

Then, thump. A silent, unmoving pile of clothing and limbs.

The firemen were here. Some of them began to raise a ladder. Others rushed out with a net and hurried to the sidewalk to hold it out under the girls as they came. The bundles of clothing broke through the net, as cleanings as Sam teaching his mutt to jump through a hoop.

The thumps sounded just as loud as if there had been no net there at all. The thumps sounded so loud that he wondered if the entire city could hear it. It felt like they should.

Józef grabbed him and turned him away from the factory, pressing his face tight against the wool of his jacket so that he couldn't see the factory anymore. Arms circled around his back, holding him there. Keeping him from turning around.

He could still hear the thumps and the screams and the screams ending, anyway.

Thump.

Thump.

Thump.

Thump.

He could feel Józef’s breaths coming in hard and ragged and unsteady, almost in time with the thumps. The heave of his stomach and chest and the choking of his voice.

"Mame," Jakub cried. "Mame!"

And then, before he knew it, just like that – it was over. The fire was out. The screaming from the factory had stopped, only to be replaced by the screaming of the crowd as they demanded answers, demanded their loved ones.

Only last winter, Mame and what felt like half the Lower East Side had gone on strike to demand better working conditions and more safety precautions and increased pay. She had come home limping, beaten black and blue and purple by batons and truncheons. And now the water running into the gutter from the firemen’s hoses was red with blood.

Józef turned on Jakub, eyes blazing. “Go!” he shouted. “Go find Tate – go now!”

Jakub hesitated.

“Go!”

Jakub ran and ran and ran, his feet pounding on the uneven cobblestones.

Blessed are You, Lord, our God, King of the universe, the true Judge.

But no matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t outrun the sickly sweet smell of burning flesh, the thumps on the pavements, or the flood of water trickling between the cobblestones in little stream. Water stained red with blood.

“Yitgadal v’yitkadash sh’mei raba.”

The words of the Mourner’s Kaddish washed over Jakub. His mouth moved, he could hear himself speaking, feel the vibrations in his throat – but it didn’t feel real.

Glorified and sanctified be God’s great name.

None of it felt real. Not Mame's death, not the way her body had been one of dozens stacked carelessly like a pile of wood outside Bellevue, not the way it had taken three days for Tate to identify her body and bring her back home, not the blackened skin and snapped-off fingers of what had once been his mother.

Her body was inside the shroud, but it wasn't Mame. Not anymore.

He could hear the rest of the burial procession join for the chorus, their voices mixing in with Jakub’s and Józef’s and Tate’s. “Y’hei sh’mei raba m’varach l’alam ul’almei almaya.”

May His great name be blessed forever and to all eternity.

It was raining. He could hear the steady drum of raindrops as they fell from the sky landed on the earth.

May there be abundant peace from heaven and life, for us and for all Israel. And let us say, Amen.

It was raining. His feet were wet as water inched its way through the seams of his shoes, drop by drop.

By the time the haunting melody of El Malei Rachamim cut through the chilly air, Jakub had run out of tears. He wasn’t sure he could cry anymore.

God, full of mercy, who dwells above.

“Al mekomah tavo v’shalom,” the rabbi finished, as that white, white shroud was lowered into the ground.

Jakub hoped that Mame had peace now.

Tate picked up the shovel.

The first scoop of dirt went into the hole with the shovel upside-down. The next, and every scoop afterwards, right side up.

Then it was Józef’s turn.

Then Jakub’s.

It was raining.

The dull thud of each clump of earth as it landed on the linen, no longer white but wet and streaked brown with mud, made Jacob flinch.

Thud.

Thud.

Thud.

That was when he discovered there were more tears left in him after all..

It was raining. He shivered, and he didn’t know if it was from the cold or the wet or something else.

He wanted to look away. Close his eyes. Focus on the leaf falling from the tree. The line of the horizon, murky and hidden by the clouds. But he couldn't not hear the thuds.

So he stood there, watching and shoveling as Mame disappeared beneath the earth, one thud at a time.

The morning of his bar mitzvah, Jakub woke up and immediately wanted to throw up.

He was going to mess this up, he wasn’t good enough at memorizing to get through both his Torah portion and the haftarah, let alone deliver a drash. Tate was even going to take the morning and part of the afternoon off from work and his pushcart in order to watch Jakub be called up for aliyah for the first time.

Józef, already awake and attempting to blearily shave with cold water from last night’s washbasin, muttered, “If you throw up on the bed, you’re the one doing laundry tomorrow.” He hissed as the razor slipped and opened up a thin line along his jaw, then splashed more water over it and walked over to Jakub. “I can do this, I know you can. Come on, get dressed, now – can’t have you being late to your own bar mitzvah. Tate will be waiting for us at shul.”

Jakub swept a tallit over his shoulders and carefully wrapped tefillin around his arms for the first time. Tate had worked extra hours, and Józef, too, as a newsboy after school, to buy him his very own set.

Tate said, “Baruch she’petarani me’onsho shel zeh,” over him. Then, he quietly whispered in Jakub’s ear, “Your mother would be so proud if she could see this.”

Jakub recited the Torah portion – the red heifer and and the deaths of Aaron and Miriam and Moses striking the stone and the battle against the Ameleks and the final great battle against the Emorites before entering the land of Israel.

He chanted the haftarah about Jephthah, someone once shunned, but then regained his rightful place in battle.

He managed to not drop the Torah scroll, the yad stayed where it was supposed to and didn’t jump any lines. He even got through his drash, which Józef had helped him write, without stumbling over his words or skipping any paragraphs or wandering off topic because he had forgotten what he was actually supposed to say.

And as Tate and Józef lifted him up in a chair for the hora dance, it really sunk in. He hadn’t messed this up. He was a man, now.

Tate never came home for Shabbos supper one Friday night.

Jakub could count with the fingers on one hand the number of times he would see Tate on any given day, or even a week, sometimes, but Tate was always home for Shabbos supper – even if he had no choice but to be back at work the next morning.

Józef, home from classes with a few hours to spare for supper before his ferry shift, went out to look for Tate – telling Jakub to stay home in case Tate was just late.

By the time Józef came home, Shabbos supper had long since ended and most of the other tenants had either gone to bed or left to work a night shift. Jakub couldn’t sleep, though, so he sat outside in the hallway, using his hand to brush as much dirt away from the wooden floor as he could before sitting down with a textbook.

Final exams were in only a few months, and eight grade meant the end of elementary school. The only thing after that was high school, and then after that, university. Jakub wasn’t sure he felt ready for high school, but he had to go.

Brandywine. Great Meadows. Lundy's Lane. Antietam. Buena Vista.

Battles and wars and dates and dots on a map and letters on the page swam and blurred together in his head. Who won and who lost, which side fought for what cause. Every time he lost track of which battle had been part of what war, he made himself start the recitation again from the top of the list.